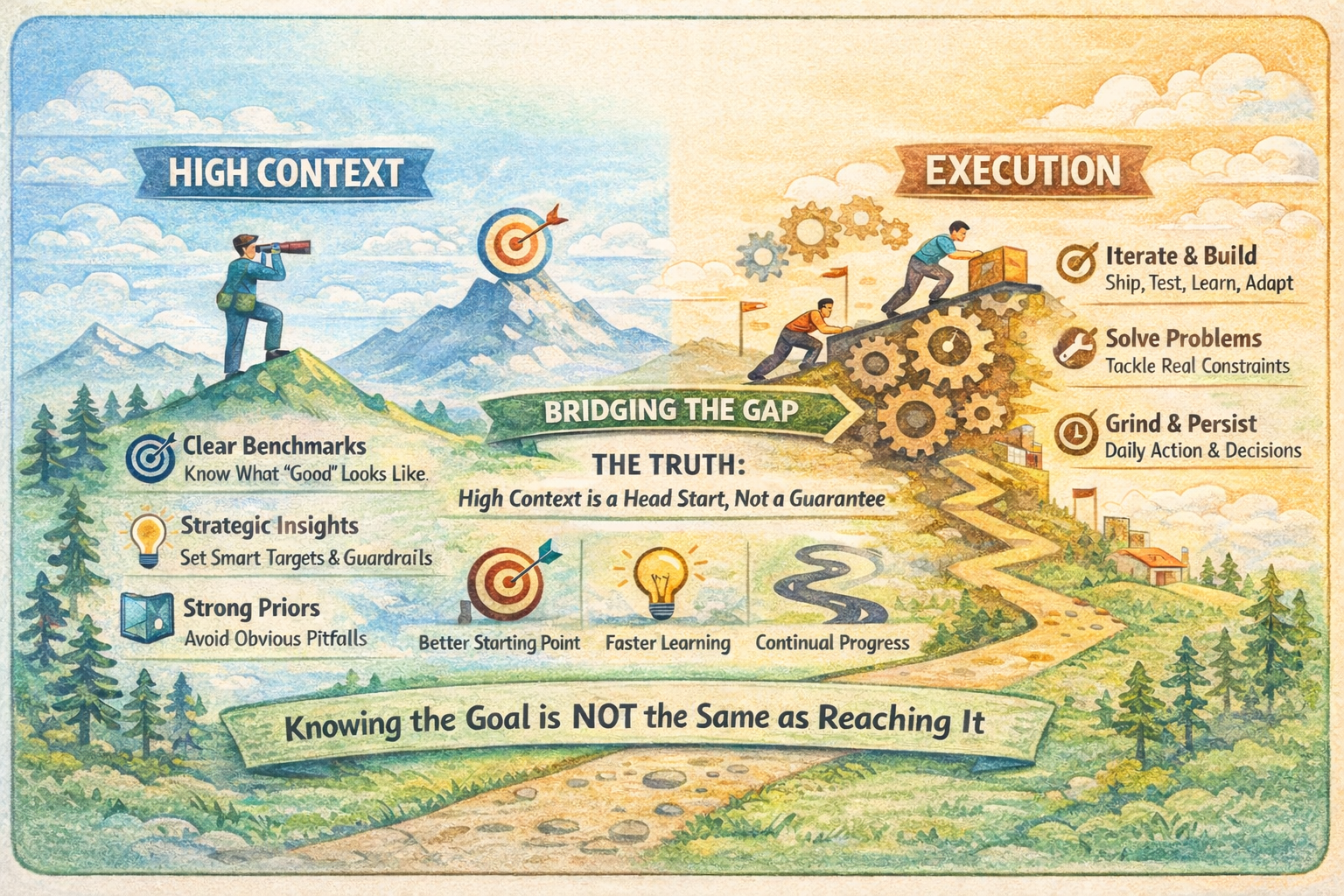

High Context Is a Head Start, Not a Guarantee

A pattern has become increasingly visible across the ecosystem: people with unusually high exposure to company-building are choosing to build companies themselves. Sometimes it is investors moving from evaluation to execution. Sometimes it is repeat founders doing it again with sharper instincts. Sometimes it is domain experts stepping out of a decade-long operating career with a clear view of how the industry really works.

The default reaction is predictable: if you have seen enough businesses up close, surely you will build a great one: high context in, high outcomes out. There is a kernel of truth in that belief, but it is incomplete. High context often gives you something valuable: a clearer sense of what “good” should look like at each stage, and which trade-offs tend to be worth making. It reduces the search space. It improves your starting point.

What it cannot do on its own is cross the distance between an informed target and a working reality. That distance is execution.

The useful distinction: knowing the optimum versus reaching it

High-context people often know the “optimal ranges” a business should converge towards. They have seen enough examples to develop an internal benchmark for:

What healthy retention or repeat behaviour tends to look like in a category

What a sensible payback period or gross margin profile might be

What a credible sales cycle and conversion funnel could be

What “good enough” product quality is for a first wedge

What an operating cadence looks like when a company is actually compounding

Exposure typically builds declarative knowledge: what good looks like, what tends to work, what tends to fail. This is not trivial. It is a genuine advantage. Many first-time founders spend months, sometimes years, discovering the basic contours of what good looks like. High context can compress that discovery. It can help you avoid expensive detours.

But there is a second, harder problem: reaching those ranges in the first place. Execution is largely procedural capability: making decisions with incomplete information, shipping under constraint, selling when you are tired, hiring when you are wrong, fixing what breaks, and doing it again tomorrow. The path is not linear, and it is rarely clean. It is shaped by constraints, timing, team, distribution, and the sequence of decisions you make when reality disagrees with your plan.

Why high context helps, across investors, repeat founders, and domain experts

High context tends to create three durable advantages.

1) Better priors, fewer dead ends

You start with more accurate assumptions about customers, pricing, channels, and business model risks. You may still be wrong, but you are less likely to be wrong in predictable ways.

2) Stronger constraints

You have a clearer sense of what not to do. This matters because early-stage companies fail as much from dilution of focus as from lack of effort.

3) Faster calibration of “progress”

You can distinguish activity from progress. You know the difference between shipping and learning, between traction and noise, between a good month and a repeatable motion.

These advantages show up for investors, repeat founders, and domain experts in slightly different ways, but the common thread is the same: context can move you closer to the right questions earlier.

Why it is still not a guarantee

The gap is not intelligence. It is friction.

Execution is where the business reveals its true constraints: customer hesitation, product edge cases, sales objections, hiring mismatches, cash timing, operational surprises, and the psychological grind of repeated small failures.

High context can even create specific failure modes:

Overconfidence in the map: If you believe you already know the market, you can skip the uncomfortable work of re-validating it. You end up “executing” against assumptions that were never properly tested in your context.

Confusing critique with construction: Being able to diagnose weaknesses is different from building systems that prevent them. In practice, the job is less about spotting flaws and more about designing feedback loops that correct them.

Optimisation too early: If you know what “optimal” looks like, you may try to engineer for it prematurely. Many businesses need a phase of messy learning before they earn the right to optimise.

Underestimating the cost of attention: High-context people sometimes carry more mental models than necessary. That can become indecision dressed up as sophistication. Early-stage advantage often comes from committing to a narrow wedge and learning aggressively, not from perfect strategy.

So the honest claim is not “high context does not matter”. It is: high context is a head start that only pays out if you can convert it into repeated, grounded decisions.

Knowing the optimum is direction. Execution is navigation.

If you want a clean mental model:

Context helps define targets and guardrails. It answers: What should we aim for? What is plausibly true? What tends to break?

Execution builds the machine that moves you from today to those targets. It answers: What do we do this week? What did we learn? What changes now?

High-context founders can be unusually powerful when they treat their context as a tool, not a verdict. They do not assume their priors are correct. They use them to design better experiments, faster.

The conclusion worth printing

Relevant exposure can make you faster at forming hypotheses. It does not make those hypotheses true.

High context can place you in a strong starting position. It can help you see what “good” looks like earlier than most. It can reduce expensive mistakes. It can compress time.

But it does not substitute for the compounding work of building: the unglamorous cadence of shipping, selling, hiring, deciding, revising, and doing it again.

So no, relevant exposure does not equate to success. But it often equips you with something rare: an early sense of what “good” looks like. For investors, repeat founders, and domain experts alike, that clarity can be the difference between wandering and building. Execution is what turns it into reality, and when it clicks, it is a powerful combination: better starting assumptions, faster learning, and momentum that stacks.

– Nankee Hari, Equanimity Investments